Here is the transcript of our guitar chat. Lot’s of great advice in here.

Leo: So we were going to talk about common mistakes that guitarists make. Do you have any that you could offer us as tips?

Yuri: Maybe we should break it down into young guitarists, beginning guitarists… Actually, among all ages and especially beginners, if they do not have a great teacher or are self-taught, a most common mistake I see in the left hand is flat or inverted wrists.

Leo: Hyperextended?

Yuri: Yeah, they don’t have the correct arch. So the way I think about wrists, the right and left hand should have similar arches. I also personally prefer a little bit of arch in the right hand wrist. It gives me more power and gives me more control rather than the straight wrists. But I think it also varies with the ratios and proportions of someone’s hands. In general I do think I can get more sound. It also changes the angle with which you attack the string. So another issue related to the left-hand is that many students keep the inside the knuckle or the inner side of the palm too close to the curled first finger and to the bottom of the fingerboard. That shortens your potential reach and it actually puts a lot of strain on your pinky because then you end up using the [the tip] joint.

Leo: The furthest joint instead of the near one?

Yuri: Yes, the knuckle joint, and that can lead to injury. Or what I often see is people bend right at the tip joint. So I see a lot of calcium buildup right here [points to left hand pinky tip joint], I’ve seen guitarists that have that, and that has to do with a not ideal position of the left hand. I view each finger as an equal, so they all should kind of follow each other’s shape. So when you see something out of balance then it deserves attention. Another issue is the inability to play on the tip of the finger. Instead, beginners tend to use the pad. So what I usually recommend for my students is starting with a very simple exercise where you don’t even have to play. So you just start with one, you add two, and try to keep exactly the same shape, and then the same thing backwards. So just one, two, three ,four but what’s important is when you release your fingers you don’t do this [fingers splay away from neck]. You stay controlled and that really helps you learn to control the movement. [Exercise is simply placing finger 1 on a fret, then 2 in the adjacent fret, then 3 in the next, and then 4 in the next. The hand stays still.]

Leo: So that’s a good one for just general left-hand hygiene, right?

Yuri: Yeah, and I like to start it around 5th position or 7th, and the reason is because right here there is no[right arm pronation] like when you play in the lower positions. You are not coming at an angle like this, your forearm is actually more perpendicular to the fingerboard. And actually the 7th fret is probably … 7th or 8th, where you can really have arm at 90 degrees [to the neck].

Leo: And also there’s much less extension, too.

Yuri: Right, so it requires less work from your left hand. And you can just do it on one string, or you can do it on all strings. Also, another exercise is something as basic as putting one finger down and taking it off, and putting another finger and taking it off, that’s not as easy as it may seem. Having that isolated movement is also important, to kind of analyze how the finger moves. Because it has three joints, and I like to think of it as distributing the energy over all the joints, rather than overusing one of them. Like you don’t want just one joint and keeping the other one like this … it’s kind of all of them working together.

Leo: Would divide the energy evenly through all three joints? Or would the proportion shift to primarily come from a certain joint depending on what you were doing, like slurs?

Yuri: I do think the knuckle is the primary joint, and the power should come from … well actually that’s a whole other topic, where a lot of people press with the thumb and they don’t use a lot of the knuckle muscle. Because you pretty much don’t need your thumb to play. It’s just there to …

Leo: It’s like a balance or pivot somehow.

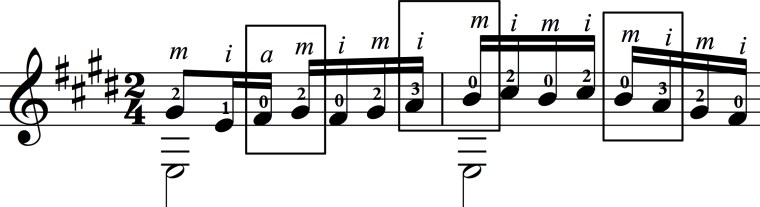

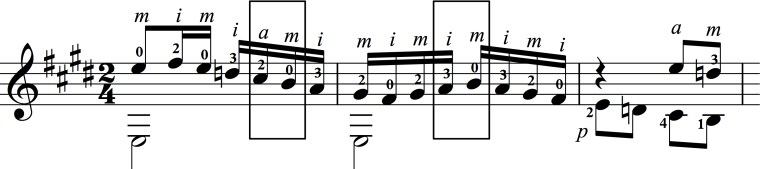

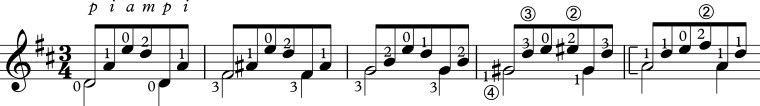

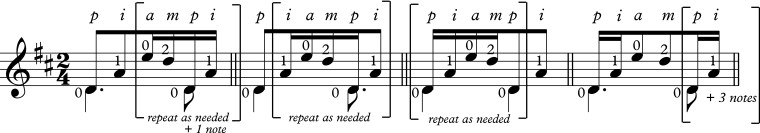

Yuri: Right. But you don’t hold the guitar. I’ve had students say, “Well if I don’t press here I feel the guitar is going to fall off.” Sometimes it’s psychological. From playing power chords and not doing them the right way. Usually what I do when I warm up, I combine left hand and right hand. So for example … maybe we should talk a little bit about right-hand exercise [see first video in previous post]. So actually that’s the last step of that exercise. So the parts of it are using one finger [see 2nd video] and then doing the same with a [see 2nd video] and then the same exercise except using m and a.

Leo: Do you do ia as well?

Yuri: No, I find that i and a have really good separation.

Leo: Just by doing the two other pairs [im and ma] they seem to …?

Yuri: Well, in general I find that I don’t have to work much on ia. I think i and a are separate joints anyway. But I do find that making even pinky stronger is helpful. It really helps me actually when I start playing with one finger. And then eventually when I get to the end of my warm up I start doing im. So I start with the hardest thing possible. One finger, m and a, sometimes pinky. And then eventually I get to im and it feels so easy.

Leo: Natural.

Yuri: Yeah. Like I started working on [Villa-Lobos’] Etude No. 7. And I would just play the scale with i and then I’ll play it with m and only at the very end will I play it with im. So that feels much easier at the end. Oh, and also, I work on extensors [see 3rd video]. That helps, too. Like you can do the same exercise. [playing] Or maybe not that on the 6th string…

Leo: Yeah, it’ll destroy your nails.

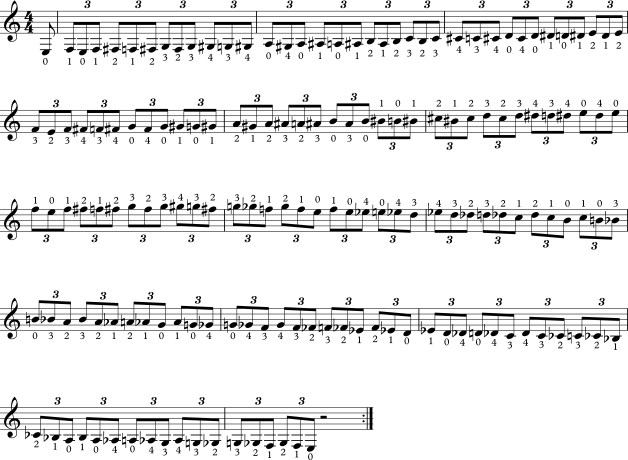

Yuri: This really does help too. [see 3rd video] Also I like to do ami scales. So, for example, any scale, always going ami.

Leo: So a does all the crossing? Or does it just depend on the …?

Yuri: No it’s just always that pattern: ami. And you can start with whatever finger you start. And in the beginning once you start developing this technique it’s difficult to keep track of which finger is next, but over time it becomes so automatic.

Leo: Great. What great advice.

Yuri: Well, you know, I know pretty much all of us—all guitarists—want to develop better scales, have more accuracy, play faster. How do you push that? How do you consistently get better at that? I think these exercises are pretty much it, not the secret, but the way, to get better at it.

Leo: And do you do this using a metronome?

Yuri: Yeah, sure. I mean, the more you do it the better, of course. The more precise you are the better it is. I mean, there’s a danger of course of doing too much of it. You don’t want to injure yourself. So you’ve got to build it up over time. And you’ve got to be very disciplined about doing it every day, a little bit, and seeing how you feel. Because if you overdo it … that’s the major mistake I find by many teachers, who are just like, “ Oh, just do these exercises and you magically will start playing better.” Or, “The more you do the better you play.” I don’t believe in that, I think there is a sweet spot of how much you have to do before you start feeling fatigue in your hand. And when you do start feeling tired you do have to take rests. Stretching is very important. I mean I have some experience from getting injuries, but now I know, basically, that’s red zone, don’t cross over there.

Leo: They say the same thing with running mileage. That you can’t go out and run a marathon, right? You have to slowly build it up, and never increase mileage by more than 5 or 10% a week or 2 weeks.

Yuri: Well, I’ll give you a perfect example. I have a trainer, I work out with him for an hour a week. And I’ve worked out before, but it wasn’t with a trainer, it was all by myself. And I would find myself getting frustrated. I would work really, really hard one day, and my whole body would ache for another week, and then I’d be like, “Well, I can’t do anything because my body hurts.” And then you come back and you’re just not motivated. And so, with the trainer, he would give me just enough so that I would feel some fatigue, but not to the point where I didn’t want to come back. But over time he started increasing and increasing …

Leo: the physical demand…

Yuri: the intensity, yeah. And I think that playing should be exactly the same way. Taught the same way.

Leo: But it’s difficult, because you’re often training yourself. And so, if you don’t have a teacher or you’re a professional, you have to have this fine understanding of what you’re doing.

Yuri: Yeah, and often if you don’t have a good teacher it’s very difficult I think, to gauge. Because we all think the more the better. But not always. There has to be the right amount.

Leo: And intellectually, too. Not just physically, right? You only have … or at least I know I have limitations in terms of how much I can focus. I can go strong for an hour or two and then I need a break, and another hour or so. But if I hit 4 hours, I think that’s about the limit of the psychic energy that I have available for intense practice.

Yuri: Yeah. And sometimes you will be practicing and you’re not really accomplishing anything, you’re just simply playing the piece. Which in itself, yes, it’s beneficial, but I think if you compare it to concentrated and focused practice, it’s much, much better to do that rather than just noodle on the guitar.

Leo: Right, I feel the same way. You’re better off going to do something completely different.

Yuri: Yeah. Because sometimes in half an hour you can accomplish more than in two hours, if your head is not in it, your mind. Yeah, it’s like, the secret is just consistency and regularity in practice.

Leo: Do you take days off?

Yuri: I do, when I’m overloaded with teaching (laughs). I still try to at least play somewhat. I try not to skip days.

Leo: If you have a limited amount of time, like just one hour, say, what do you tend to focus on?

Yuri: What I would sometimes do, I would pick a small passage or I would pick a small scale, or even just do one of those exercises I was doing, reconnecting with myself, with my hands, with the guitar, with the feeling. It’s very, very important I find, to connect with the mechanics of playing, and if you have that connection you can pretty much play anything. So I try to maintain that. Not necessarily a specific piece.

Leo: But just the feel of what it’s like to be mechanically on…

Yuri: Yeah, at the end of my practice I want to feel that, yes, I can play anything right now, my hands are capable. Well, it’s also interesting if you don’t play for a while, and I don’t know, it happens to me, I start thinking, “I just don’t know how to play anything. I forgot how to do this.” It’s like when you lay in bed for a day, and you start wondering, “Can I still walk?” But the fact is, yes, we, I mean certainly professional guitarists or musicians, we’ve been playing for so many years, for so many hours, the chances of us completely forgetting something are very, very low. But I think there’s something psychological about the daily practice that makes us feel that we can do this. Yes, better or worse, but if you don’t do it for a few days you start really thinking, maybe I just …

Leo: I lost it, right?

Yuri: I think there’s an element of magic to playing. It’s not all completely clear to us what is … how it’s happening. That’s what I think. When you sit with the guitar it’s like “Oh, wow, this is incredible.”

Leo: It’s a box of wood and some … it’s like a drum in some ways. What about, you know, common mistakes, just to come back to that. You were mentioning a couple of things for beginners. What about for conservatory students, or students that you’ve taught master classes to?

Yuri: Oh, sure. You know, one of the most often mistakes that I see … or, not mistakes, just underdeveloped ability to be able to play evenly. And that evenness could be developed. I like to think of it as a clean slate. So being able to play on the beat. So playing in time. The other part is having control of volume, and having the control of tone, having consistent tone. Being able to change your tone when you want to, as much control as possible. That’s why fingerings are extremely important. I often think of fingerings as … each finger has a different position on the string. Of course you can move your hand as a whole, but i will always be more towards the left, m will be towards the middle, a will be more towards the right. So ideally people’s i finger should have the warmest tone. Because it always happens to play near the soundhole unless there’s some problem with the nail of course. But generally, i should always be the one that you should look for to get a nice tone. m for me is the power finger. It’s longer, it’s also a little brighter. And a is like the third wheel [laughter]. It’s like it’s there to help you reverse the fingering, or it’s there to play the arpeggio or play tremolo. So it has a very different function. And I know some players actually never use a, or try to minimize the use of a. I don’t know if I completely agree with that. I think a is a good finger, and it definitely has to …

Leo: It deserves to be part of the game [laughter].

Yuri: Right, right. [laughter] But it has its own function.

Leo: So overall you would say that controlling your volume and balance and rhythm, that should be something that students should focus on?

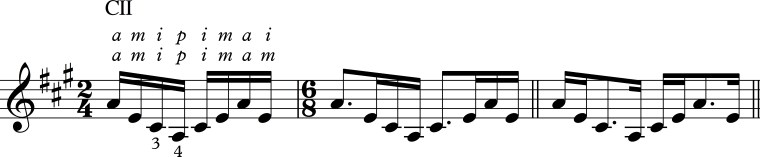

Yuri: Right, well I can give you a little example [see 4th video]. Let’s say Etude 1, Villa Lobos, right? So obviously the pattern is this. [playing] Now what I often hear is unevenness, let’s say [playing]. It’s a little chaotic. Now what I would like to start with is having all notes even. [playing] Then we can start talking about shaping the phrase. The way I see it is, it’s going up, it’s going down. There are also little accents on every other note, where you hear this … actually, the fingering that is chosen, pi in the beginning automatically adds a little weight to the first, third note, every other note [playing] right? So not a lot is needed to be added to make it sound …

Leo: Musical and controlled.

Yuri: Right. So we can use whatever is already in the pattern. If I don’t do anything, if I simply play notes evenly, it will still be there. [playing] So that’s the beginning step, where you try to make everything even rhythmically, even in terms of accents and having control, and then you decide on the interpretation. The other problem with this piece is really interesting. When you play it, the higher you play, the further down you press the strings. So what ends up happening for the right hand is the strings get displaced. And on top of it there is another issue of pressing hard with the left hand, so having tension in the left hand transfers to the right hand, and that’s when the right hand gets confused and starts making errors. So, keeping left hand in check, tension in check, also practicing right hand alone, making sure it will be able to sustain the changes of the left hand, the misplacements … not misplacements, but being able to adjust to the …

Leo: The slight adjustments of the strings. The depressed strings.

Yuri: Right, right. Keeping in mind that the higher you play, the more careful you have to be. Of course when you play here [lower positions], the changes over here are not very significant. Yeah, I discover all these things actually from teaching.

Leo: Yeah, you notice it, and you try to solve it for a student, and then you’re like, oh, good to put that into practice.

Yuri: Actually another issue … well it’s not an issue, but it’s a quality of guitar. The higher you play, the more on the sharp side the note will be. That’s what the compensation is for in the saddle and the nut. But yeah, the higher you play the more out of tune you’re probably going to be.

Leo: Do you use etudes as warm-ups? Or do you tend to focus on very basic but perfect movements, and then you move on to your repertoire?

Yuri: I usually take elements out of etudes. I don’t think I get much out of just playing them but it depends on the etude, of course, but generally I try to save time by playing just shorter passages.

Leo: So you wouldn’t, say, play through an entire piece to gauge your mechanics? You know, to sort of touch base with where you are physically, or …

Yuri: I think if I’m really practicing a lot, I would do that, because I want to also feel my stamina, how am I feeling, because if yesterday I was able to play a whole piece, I should be able to do it today as well.

Leo: That’s a lot of very, very good advice. Just to shift gears a bit, one of the questions that I imagine most guitarists would be interested in knowing is what steps you take or that are very clear to you when decide to learn a new piece?

Yuri: Steps in learning them?

Leo: Yeah, in absorbing a new piece.

Yuri: Well let’s say if … it also depends on the piece. If it’s a piece that has been played before, if I’ve heard it before, or if it’s a new piece that nobody else has played, I think the approach is a little bit different. If it’s a more traditional piece, I will usually try to listen to the original. Say it’s written for a different instrument, if it’s a transcription or an arrangement I will usually listen to the original. And more than one performance. If it’s a piece by Bach, like a violin sonata I will listen to it on violin. If it’s a new piece I can’t do that, so you have to live with a piece for a while. You have to perform it, you have to see what works, what doesn’t work. But at some point you do have to take it on stage, and take the risk, and see how it goes. But generally the process for me is always … my fingerings have to be defined. So I never leave a single fingering up to chance.

Leo: Right. You have to know exactly what each hand is doing at all times.

Yuri: Right, and I have to also know, why is that fingering there, what’s the purpose of that fingering and not the other finger on that note. So there are many, many decisions that have to be made before I can even play the piece. Now, the decisions about making those fingerings, they’re very … they’re not an easy thing to explain, and every guitarist has their own way of thinking about fingerings, different experience, different hands, different nails, different experience with discovering what works for them, different repertoire … so of course everyone has different preferences. But there are some things that are not up for discussion for me. So that has to do with posture. There is not that much variation in regards to posture, or how the fingers should move in a way to minimize chance of injury and to optimize efficiency. So there’s really not that much room. And there used to be, you know, the Segovia right hand, today nobody really plays that way. So that went away, and I think many other things eventually will also fade out, because they will prove that they’re not efficient. But with the guitar being a new instrument, it will take some time to get to that place. Unlike piano or violin, where it’s not up for discussion. The teacher will basically not work with you, and say, well, study with somebody else …

Leo: You can’t develop your own technique on piano.

Yuri: Right, right. This is a hundreds-years-old tradition, and there is a reason why things are the way they are. The chances of you coming up with something really new related to how we use human body on these instruments is very low.

Leo: Exactly. Unless you don’t have the usual human body.

[laughter]

Yuri: Unless you are an alien…

Leo: And so once you have fingerings and you’ve gone through that process, what’s the next …

Yuri: Well the fingerings process is also …

Leo: That almost makes you learn it, right?

Yuri: Yeah, but at the same time, fingerings and interpretation are so connected. So that when I make decisions about fingerings I also think about, what is this music about? What is this phrase, what am I trying to do with this phrase? Should it be rest strokes or should it be free strokes? It’s not only the ease of playing, it’s also, what is the gesture I’m going after? Is this intense gesture, or is it a light gesture? Should the phrase end with a rest stroke, is the last note important of a scale or of a passage? How fast does it need to go? Is this arpeggio pattern going to allow me the easiest way to play it fast, that passage, at the tempo that’s required? And sometimes you say, I will give this a try, I’ll play it for a while, see if it works, or eventually you may replace it with a different fingering. Many, many masters will change fingerings as they get more experience.

Leo: I almost feel like fingerings are really never set in stone, except at the beginning, when you first learn the piece, and then as it evolves you perhaps will adjust, or if you re-learn a piece you’ll come back to it and choose to do different things.

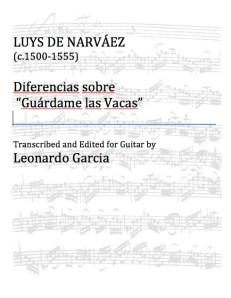

Yuri: You know, that’s a really interesting topic, talking about when we get a piece of music, it already has some fingerings, right? Now, the publisher doesn’t know the player’s experience. And the player, if it’s an advanced player, most likely they will take some good things out of the fingerings that are on the page and they will maybe change them as needed, or not … but then, if the player is not advanced, what happens then? Should the music have all the fingerings or not? And I’ve had … well when I do my arrangements, I finger every single note, every single finger. And the reason why I do that is because for a not advanced player, this is a way that works. This is one suggestion that has been given thought, that’s been tried. For an advanced player, they can erase whatever doesn’t work, they can change it, but at least they have hours and hours of thought already on the page. I also understand that a lot of publishers don’t want to spend time putting the fingerings on the page, but …

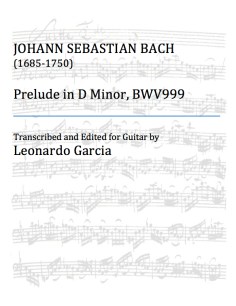

Leo: Well, there are also plenty editions out there that have horrible fingerings, that aren’t well thought out. There was a time where I was watching a master class by David Russell a long time ago in a tiny little town in a little village in the Andes, and this great player played Bach’s Prelude, Fugue, and Allegro, played it very well, but was playing mistakes because of the edition. So David Russell told the player, “I could have helped you more, but we have to fix the mistakes of the editor instead of yours.”

Yuri: Well the other interesting story is Segovia’s masterclass, have you heard that? Of course. Where, “Oh, you’re not playing my fingerings? Just, that’s not going to work, come back later.” [laughter] So I don’t know.

Leo: It’s a different era.

Yuri: Well it’s a controversial topic. Especially when the ego gets involved.

Leo: Then there’s no hope. [laughter]

Rule 2

Rule 2