If you all were inspired (or recovered) from watching Ekachai Jearakul whip off Heitor Villa-Lobos’ Etude Nº2, you may find this post helpful. While I was a student at the New England Conservatory, the second half of one of my degree recitals was simply Villa-Lobos’ Twelve Etudes. While some of the etudes are manageable, others require relentless and careful practice, and they all have moments that can fill endless practice hours with frustration. To add to the matter, I was studying with the great Eliot Fisk and despite all of his valuable advice and help, watching him display what was possible on a regular basis conjured both extreme inspiration and a sense of hopelessness at achieving such a level of comfort with these pieces. Needless to say, the year preceding that recital, I was immersed in a figurative amazonian finger jungle and found my own way of surviving.

For those working on this particular etude, there are a few spots where I found less obvious fingerings less problematic. These solutions are personal but if the spots have been frustrating for any of you, give the following solutions a try.

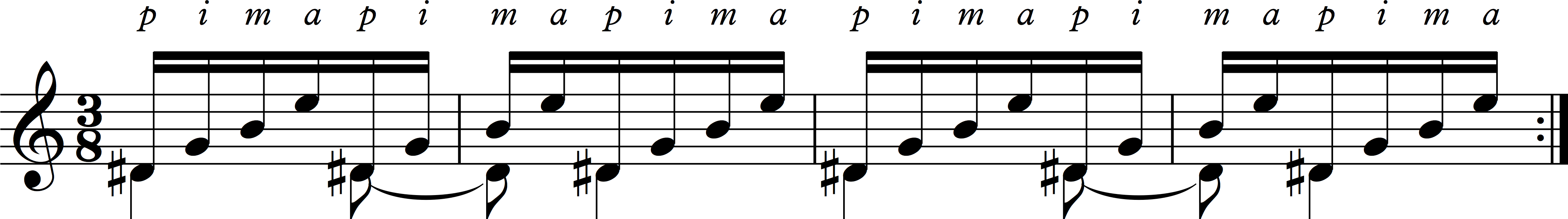

Measure 3 (repeats not counted)

In order to increase the resonance, I like having the 3rd and 2nd strings open on this one so I shift to 5th position to enable this. There are a few alternate right hand fingerings to explore but I prefer the 1st.

Measures 10-12

In this solution, guide fingers are highlighted in red. While the right hand solution is personal, I like switching to rest-stroke on the highest note of the run. If you prefer to play free-stroke, you might choose to switch to 1st position by playing the first note of measure 12 on the 1st string open and using that to shift. The second finger would still work as a great guide in this situation.

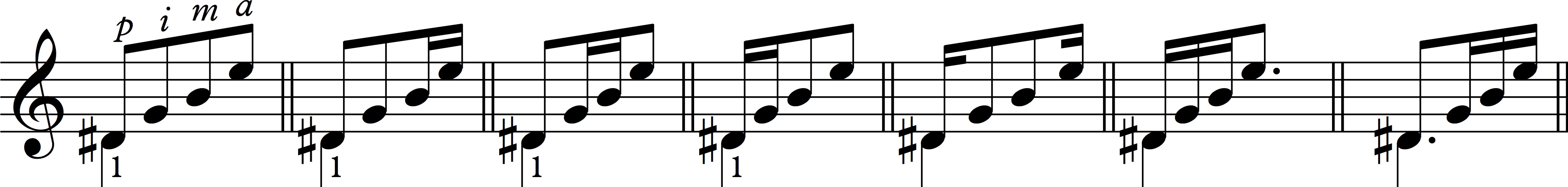

Measures 21-22

In this example, ending the repeat with a slight alteration makes a noticeable difference in playing measure 22. Again, I’ve included some alternate right hand fingerings for exploration but I prefer the 1st.

Hope this helps!

Make a one-time donation

Make a monthly donation TO SUPPORT CONTENT CREATION

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly