I thought I would take a moment to stress how important it is to know how to apply the principles from the last post to identify and problem solve mechanical weaknesses in repertoire you are working on. Because I am working on a lot of music by Agustín Barrios Mangoré (1885-1944), I thought I would use two examples of passages you all may be familiar with. I have played the music of the great Paraguayan virtuoso for decades and I still find it fun to work on. I especially enjoy his works with perpetual motion activity. Barrios’ Estudio de concierto, Las abejas, La catedral’s allegro, Danza paraguaya, and passages from his famous waltzes are perfect pieces to spend hours on. So, for this post, we’ll focus on using rhythms to strengthen our understanding and facility of the patterns in these pieces.

Estudio de Concierto

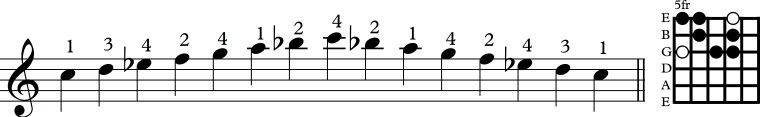

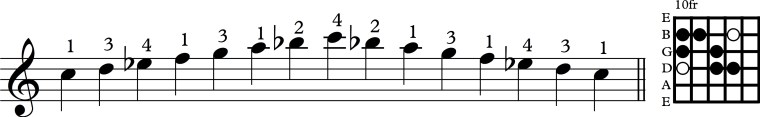

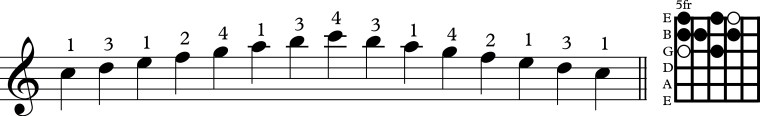

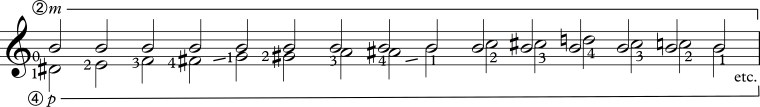

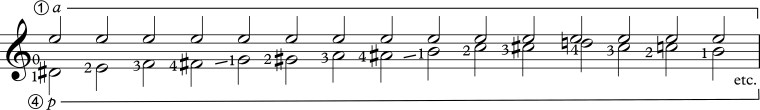

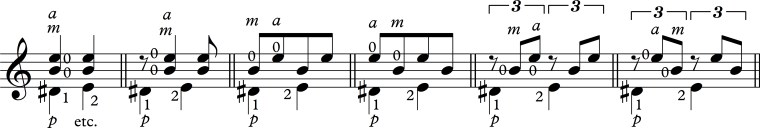

The following example illustrates 5 rhythms in which to work the arpeggio pattern for Barrios’ Estudio de Concierto. Begin by choosing the right hand fingering that most suits your technique. Whether you know the piece or not, practicing each measure in these rhythms will help develop the comfort of playing the arpeggio faster than if you were to only play in a straight rhythm, though it is necessary to do this as well (!).

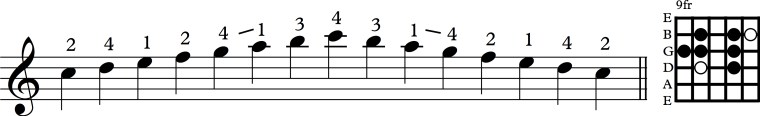

Arpeggio Fingering Rhythm 1 Rhythm 2

Rhythm 3 Rhythm 4 Rhythm 5

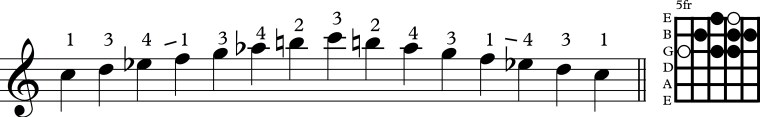

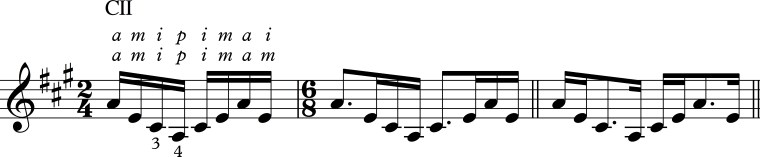

Vals Op. 8, Nº4

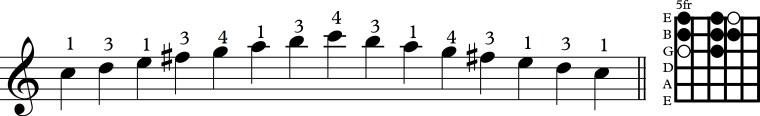

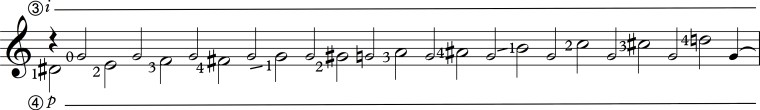

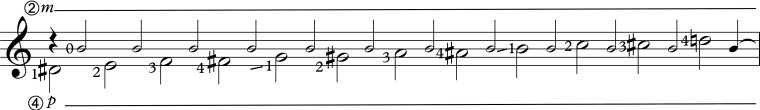

Here is the campanella passage from one of my favorite pieces. This passage deserves more writing but for now I will limit myself to rhythms.

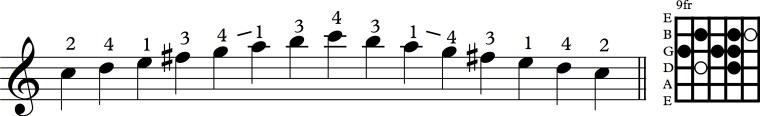

Because I know this piece well, I use rhythms to warm up and will often play through the entire section of the piece in as many as 16 rhythms. Here are four that I like to start with:

Rhythm 1 Rhythm 2 Rhythm 3 Rhythm 4

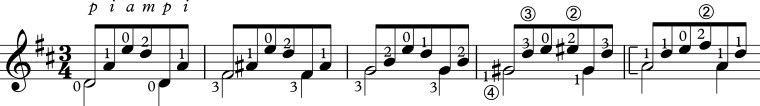

Do not feel obligated to go through the entire passage. Instead, spend some time repeating certain groupings in an attempt to make them feel natural and ultimately easy. You may find that you are better at some and that certain patterns remain sticky. Work on the sticky ones.

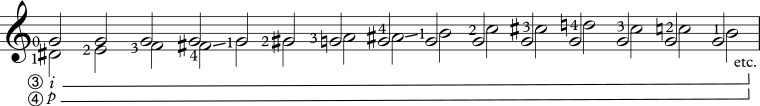

And, if you are not exhausted by this point, here are some additional groupings (notated in shorthand) rotating two eighth notes (represented by a space) through sixteenth notes:

pi am pi, pia mp i, pi ampi , p iamp i, pi a mpi

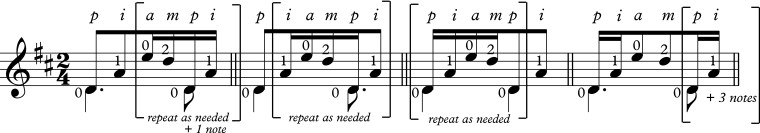

Or rotating a triplet of sixteenths with 3 eighth notes:

p i a mpi, p i ampi , p iamp i , piam p i

Or Using only one dotted eighth note (two spaces):

p iampi, pia mpi, piampi , pi ampi

I hope this helps. If there are any technical questions you are thinking about in your practice please leave a comment. I’m thinking about a post answering some common questions that I keep getting. And, in the future, I’m going to try to include a video to supplement the posts when I have the time. Until then!