As many of you who have devoted many hours a day to learning and practicing your craft know, our ability to learn or absorb new information as in memorizing new repertoire effectively and efficiently and our ability to practice effectively and efficiently are two different things. I’ve always encouraged students to focus on quality practice – where all of our mental resources work together to analyze, explore, decipher, and ultimately embed new repertoire into our systems, instead of hours and hours of subpar or mindless work.

The dilemma in what we do, however, if we want to do it well is exactly the need for both: ultimate engagement and long hours. Though I wish I could say that I have intellectual resources that enable me to go for hours and hours with the ideal level of engagement, I don’t. I may have the desire and the passion to play but sometimes, often times, with running a business, raising two boys, running, cooking, yoga, and life, I lack the energy. So how do we maximize the time we have with the guitar and how can we put in hours when we are tired? When do we do our learning? When do we memorize most effectively? When can we get away with less mindful repetition?

One mistake I used to make was to confuse what I was doing – was I learning a new piece, working on technique, or practicing or maintaining existing repertoire? I would try to do a bit of each but despite the hours I didn’t feel like I had made headway into any one thing. Assimilating and problem solving new material is more intellectually demanding whereas practicing technique and repertoire maintenance requires slightly less creativity. Dividing your practice into specific goal-oriented sessions devoted to only one priority is more effective at achieving mastery in a more timely fashion.

So first, we must know ourselves. There are times in the day when our brains are rested, primed, and clear to absorb new information. For me, this time is in the morning (after coffee) and the first hour or two after meditating. These are prime times to problem solve, imagine an interpretation, embed new information, and decipher trouble spots in new and existing repertoire. There are other times of day when we are not as sharp – after a big meal, minute 60+ after pushing ourselves intellectually, and pre-second wind in the evening. These may vary from person to person but I think it wouldn’t be unreasonable to assume that many of us fall into this pattern. As I get older, I find that I’m not opposed to enhancing and extending these prime times (within reason) and have found caffeine or enhanced coffee from Mastermind Coffee or Kimera Koffee, being fit, a healthy diet, and certain reputable supplements like Alpha Brain and Ciltep to be very effective.

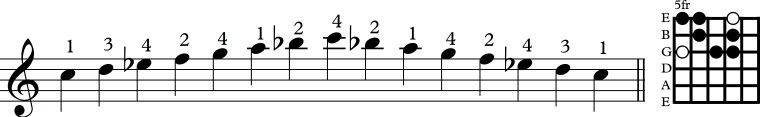

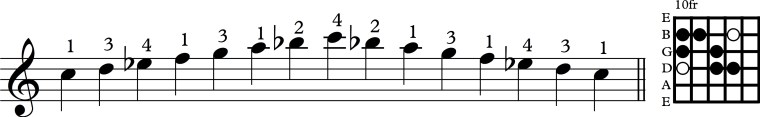

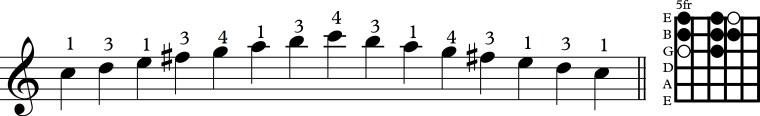

What about less mindful practice? You will get the most bang for your pluck when practicing in prime mind moments but when you slow practice with a metronome, play through familiar pieces, or try to get in the 10,000 repetitions of pimami, your brain can afford to relinquish some control to the metronome or the repetitive motions once they become automatic. The best time to do this would be anytime that is not prime. However, it is ok to use prime time for this activity though it may not be optimal for progress.

This post is becoming a ramble. So to wrap it up, practice involves many facets requiring different levels of engagement. On the more creative and mentally-taxing side, you have learning new repertoire, problem solving, visualizing, and developing interpretations. On the less intellectually demanding side you have repetition, technique work, and playing. Though resisting another tangent, I can’t help think that this may vary by individual. Is learning new repertoire easy for some while the repetition difficult? Regardless, know yourself first and then try to optimize your practice time to pair the activity with the right state of mind.