At a certain point, every aspiring guitarist tackling difficult repertoire discovers the value of practicing the right hand of a musical passage, phrase, or entire piece entirely by itself. Understanding exactly what the right hand is doing in terms of musical inflection, rhythm, and string crossing is an absolute must for mastering challenging repertoire.

The most compelling argument is that most guitarists tend to fret over the left hand and often let the right hand only play up to the left hand’s standard. Essentially, the process dumbs down the right hand, which under little practice could probably out-execute the left hand. So instead of dumbing down the right hand, enable the right hand to exceed itself by practicing its part alone and eventually the left hand will rise to the occasion of matching the right hand’s ability.

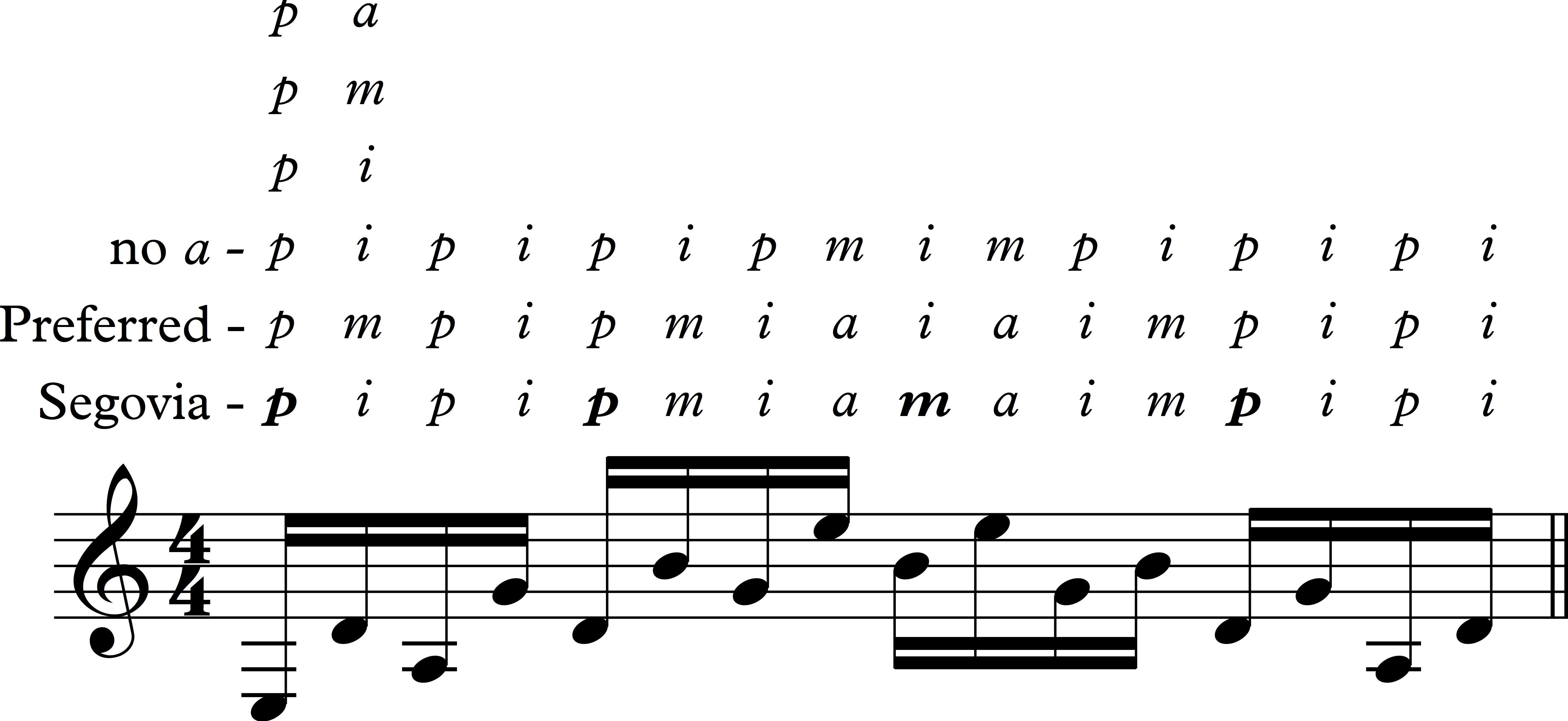

Another argument for practicing the right hand alone is that by writing out the passage as open strings, we can better see where the string crossing happens and as a result can insure that the right hand remains efficient (crossing to higher strings with m instead of i, for example) and if there is an inefficiency, that it is a conscious decision to have it that way.

Practice writing out several difficult passages of your repertoire as open strings, investigate whether or not the right hand fingering decisions make sense to optimize string crossing, and then practice the right hand alone on open strings striving to make it musical, rhythmic, and automatic. Then, invite the left hand back into the game to assess the difference.

At some point, after having practiced enough material in this fashion, you’ll find yourself able to visualize the best choice for the right hand without writing it out and you’ll even be able to play the right hand alone by looking at your score.

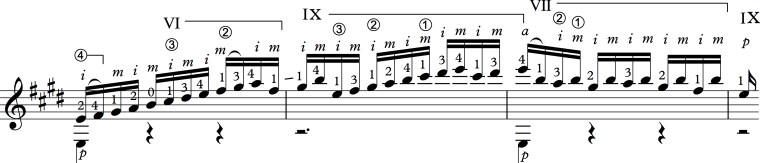

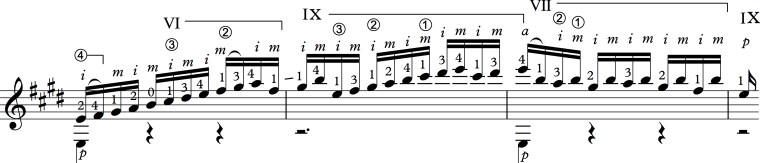

Here is an example of a passage and what it looks like after writing it out on open strings. Notice the rhythm is different to account for slurs. Also, notice all of the string crossing situations are efficient except for one situation which I’ve left for consistency in the right hand.

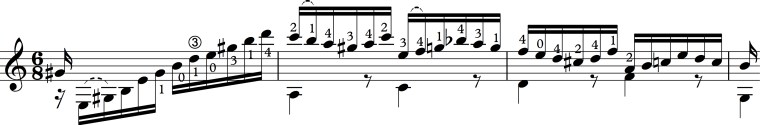

Excerpt from J. S. Bach’s Prelude in E Major, BWV 1006a

Passage in open strings (string crossing in boxes):