Here is the whole of Sergio Assad’s wonderful Suite Brasileira Nº4 from a recent concert. I love everything and every single note that Sergio’s magical pen put down for this one.

Caterete

Jongo

Toada

Batuque

Enjoy!

Here is the whole of Sergio Assad’s wonderful Suite Brasileira Nº4 from a recent concert. I love everything and every single note that Sergio’s magical pen put down for this one.

Caterete

Jongo

Toada

Batuque

Enjoy!

Here is a video I stumbled upon this morning that caught my ear. From Galerie des Luthiers in France, it features 2016 GFA Winner, Xavier Jara, playing Manuel Ponce’s Balletto. From the rich sounding Enrique Garcia guitar to the absolute beautiful and lyrical playing, Jara invokes the magical early era of the guitar. When hearing these old guitars come to life, I wish more performers would record more videos on them or, for that matter, play entire concerts on them.

The talented Spanish guitarist Andrea González Caballero just released a live video of a recent performance of Isaac Albéniz’s Cataluña from Suite española, Op. 47. Andrea’s strong, confident, and graceful playing is certainly at its best here! Enjoy.

Check out Six String Journal’s interview with Andrea here.

Thomas Viloteau‘s rendition of Roland Dyens’ Fuoco from Libra Sonatina is wonderful. As usual, his playing is technically precise, musically crystal clear, and from the looks of it, effortless. I hope he did videos of the other movements! For more on Thomas, check out Six String Journal’s interview with him here.

Time to practice!

This is an interesting technique that I have found truly helpful for developing speed and the correct rhythmic feel across whatever pattern you are practicing, and since I have not found any reference to it in the literature, I refer to it as aural refocus. Its purpose is to refocus your hearing on the larger beats within a pattern or movement, and then “feed in” the rest of the notes while retaining attention on the larger concept and rhythmic feel.

In theory, we want to perform the larger movements in time—but in practice we rarely do so because we feel limited by all the minutiae that a particular movement demands. With a lot of work, patterns that undergo the aural refocus treatment will get a boost in speed while retaining their rhythmic integrity and stability.

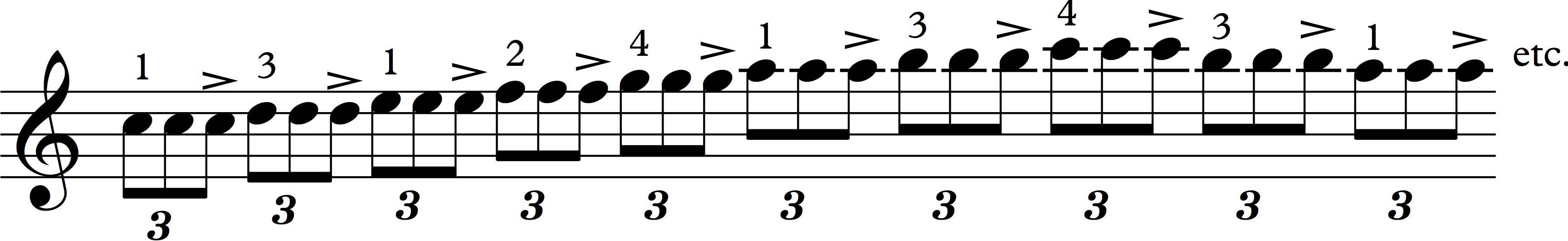

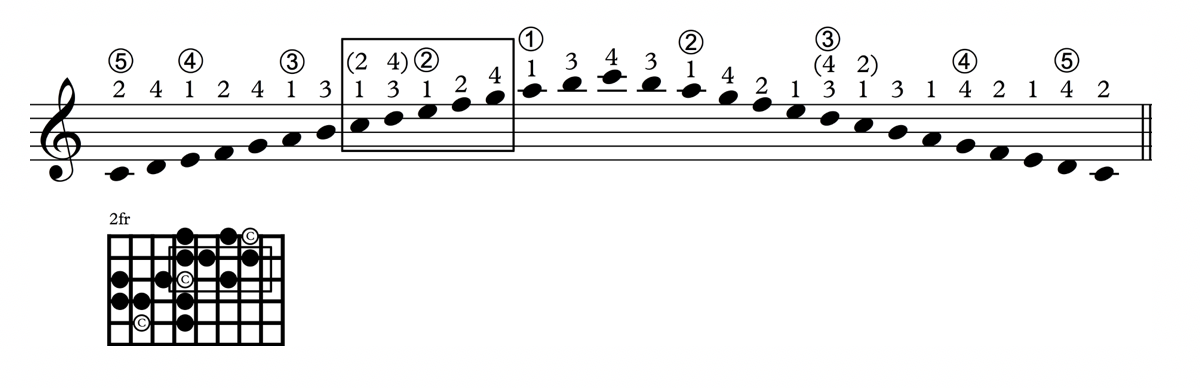

Here are three exercises for applying aural refocus to tremolo. Before you begin, set the metronome to an ambitious tempo (72–88+ bpm per half note) and keep it constant through each exercise. Play only the fingers indicated, do not play the small notes in the following exercises and feel the larger beat in the right hand. Play through each line for at least a minute. Then alternate freely between the lines, coming back to the first line often to reestablish the longer sense of pulse and technical ease.

Exercise 1

Exercise 2

Exercise 3

There you have it!

For more active practice techniques, check out: Mastering Tremolo.

By sticking a cloth or a soft sponge under the strings near the bridge, you can turn your guitar plucks into little thumping sounds. Limiting the resonance of the guitar to these not unpleasant thumps refocuses your attention on two very important qualities necessary for great tremolo technique: rhythmic evenness from thump to thump, and the quality of intensity of each thump.

So put a sock in it:

Hope that helps! Stay tuned for Part 4.

For more active practice techniques, check out: Mastering Tremolo

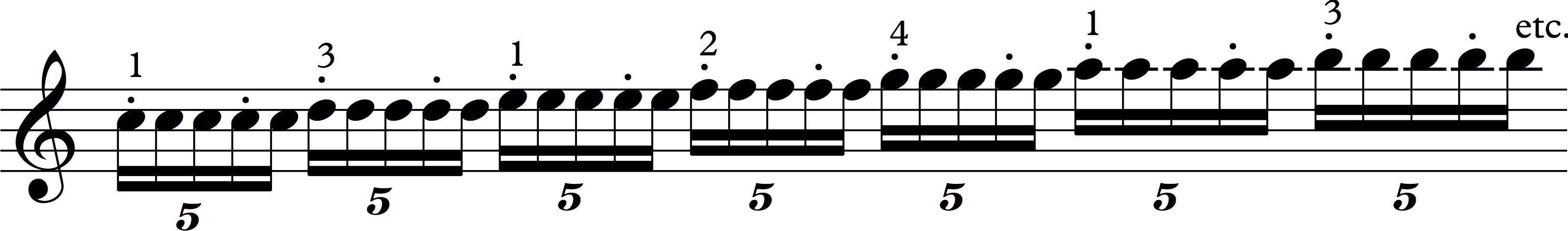

Playing through the “skeleton” of a tremolo piece helps reduce it in your mind’s ear to the essentials of what is happening on the musical front. Because we spend so much time developing the fluidity, clarity, speed, and all that goes into a beautiful tremolo technique, often our attention is so myopically focused on the minutiae of technique that we ignore the larger question of what a tremolo piece is trying to achieve musically.

There are various ways to mentally condense the way you perceive your pieces to make them seem less daunting. The most tried and true method is to play through them well hundreds of times. But because it takes time to develop the endurance and speed to perform a tremolo piece at tempo comfortably, play through them instead in an abbreviated way, as illustrated below, at faster tempos:

Another method, which I have grown to like despite the substandard sonic quality, was recommended by guitarist Philip Hii in his insightful book, Art of Virtuosity. In this method, shown below, ami act as one and pluck at the same time. Think of plucking a chord, but on one string. It won’t sound pretty, but in addition to focusing your attention on the bigger picture, by putting all of your fingers down at once you discover what position will give you access to all the strings in the most efficient way.

For more active practice techniques, check out: Mastering Tremolo

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly“I wouldn’t be surprised if slow practice is the best technique to practice in.”

—Manuel Barrueco

The effectiveness of slow practice has been confirmed repeatedly by great musician after great musician, and the principle holds true for tremolo as well. Despite the fact that performing tremolo requires great speed, practicing passages or even entire pieces at very slow tempos has numerous benefits for both technique and musicality. As Barrueco says, “It allows one to look at technique very closely.”

Besides providing the opportunity to observe technique with a magnifying glass, ultra slow practice gives the brain and fingers a chance to coordinate movements with an awareness that cannot exist at concert tempo. Slow practice allows us to hear everything that is happening on the musical front as well—harmonies, counterpoint, melodic lines, articulations, and other components that may escape our awareness at faster tempos.

But practicing tremolo in a slow and deep state of study is not as straightforward as it sounds, and what you get out of it can vary widely depending on how you focus your efforts. To begin with, you’ll need to first accustom your fingers, ears, and mind to slow practice. Play through just a small passage of a tremolo piece you are working on, and slowly build up to the entire piece. The metronome should be set to one 32nd note (a single note of the tremolo) to 42–60 beats per minute (bpm). Once this becomes comfortable and you’ve reached a meditative state of mind, try focusing on the following approaches, one at a time, as you play.

1) Fluid Movement or Gesture Focus – Despite the very slow pace, imagine the movements of the fingers in the context of the whole gesture.

2) Planting Awareness – Regulate the amount each finger rests on the string before pulling through. Awareness of the space between notes is important. If the space between notes is not even, or if some fingers plant early or late, tremolo will sound erratic even though the notes are articulated in time.

3) Deliberate Dynamic Control – Even though you would not play the piece with no dynamic variation, the ability to scrutinize and equalize the volume of each note is a skill that leads to greater control. Observe the tendency for most thumb strokes to dominate, or for notes plucked with m to lose clarity in our focus to complete the gesture.

4) Deliberate Musicality – The other side of the coin would be to include dynamics and musicality. This is harder than it sounds at such dramatically slow tempos, but focusing on maintaining musicality during slow practice clarifies musical intention.

5) Banish the Gnome – Turn off the metronome and focus your attention on the space between the notes.

Listen acutely and concentrate intensely to reap the numerous benefits of this powerful technique.

For more active practice techniques, check out: Mastering Tremolo

There are infinite ways to develop more speed, accuracy, and fluidity in your scale practice. Using rhythmic manipulation, extensor training, patterns, repeated notes, fragments, and phrasing are favorite devices. They will all explained in the next several posts. Once you are familiar with the various techniques, apply them to scales (or even troublesome spots) in your repertoire to either problem solve or build a stronger foundation.

Throughout the following series of posts use the following fingerings (basic patterns in bold) focus on efficient and relaxed alternation, tone, consistency, and rhythmic pulse. More advanced students could expand them with articulations such as staccato and legato, dynamics, and tempo. Practice the material between repeats more than twice when necessary.

Rest-stroke fingerings: im, mi, ma, am, ia, ai, p, ami, ima, imam, amim, aimi

Free-stroke fingerings: im, mi, ma, am, ia, ai, pi, pm, pa, ami, ima, imam, amim, aimi, pmi, pami

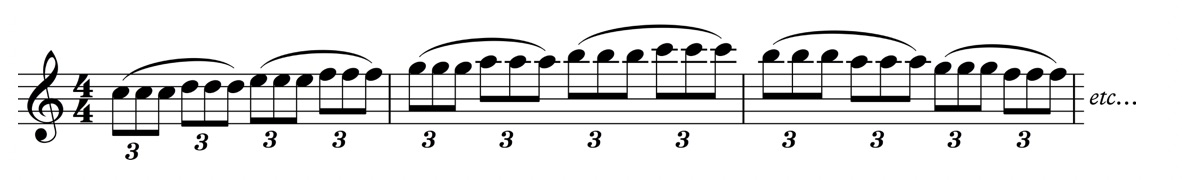

Phrasing your scales using subtle accents, articulations, and dynamics to convey note groupings is one of my favorite ways to think about music while working on scales. A slight change in articulation or accent will make your phrase move forward gracefully or plod along like an elephant. Apply the basic ideas below as a start and then apply it to repertoire.

Use accents or articulation to delineate a group or phrase:

Use dynamics:

Think phrasing:

Thanks for reading!

There are infinite ways to develop more speed, accuracy, and fluidity in your scale practice. Using rhythmic manipulation, extensor training, patterns, repeated notes, fragments, and phrasing are favorite devices. They will all explained in the next several posts. Once you are familiar with the various techniques, apply them to scales (or even troublesome spots) in your repertoire to either problem solve or build a stronger foundation.

Throughout the following series of posts use the following fingerings (basic patterns in bold) focus on efficient and relaxed alternation, tone, consistency, and rhythmic pulse. More advanced students could expand them with articulations such as staccato and legato, dynamics, and tempo. Practice the material between repeats more than twice when necessary.

Rest-stroke fingerings: im, mi, ma, am, ia, ai, p, ami, ima, imam, amim, aimi

Free-stroke fingerings: im, mi, ma, am, ia, ai, pi, pm, pa, ami, ima, imam, amim, aimi, pmi, pami

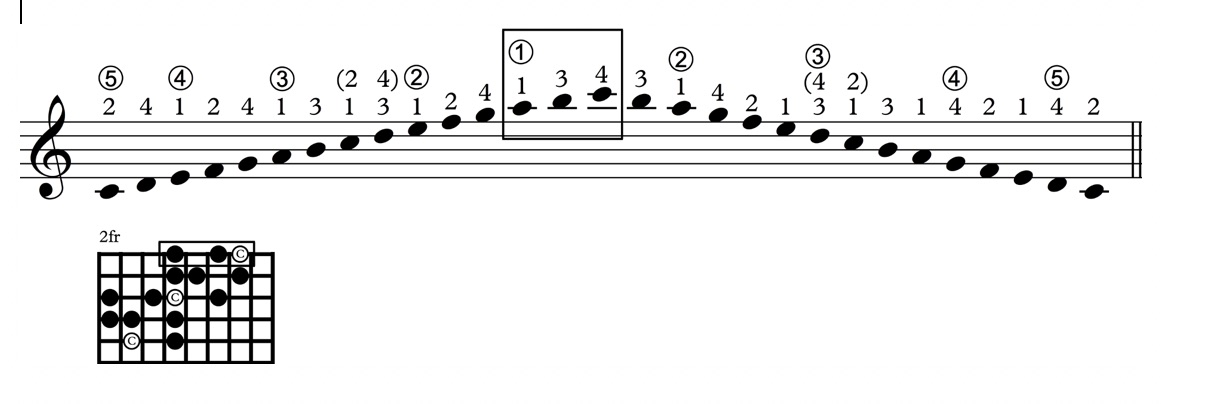

Practicing and developing the ability to play fast or expressive fragments is arguably as important as practicing long scale forms primarily because most repertoire contains small melodic fragments consisting of groups of three to seven notes. Spanish repertoire, in particular the music of Joaquín Rodrigo, is an example of where long scale practice pays off but among the music by every other composer, from Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco to Heitor Villa-Lobos, it is difficult to find many instances of scale runs beyond two octaves.

Using familiar scale forms, work on small extracts of 3-7 notes in various ways to discover which right-hand fingerings feel most comfortable and which present challenges to overcome.

Short Fragments

Step 1

Extract a group of notes from a familiar scale form

Step 2

Step 2

Develop all possibilities with incremental addition of notes.

Three notes: 134, 341, 413, 431, 314, 143.

Four notes: 1341, 3413, 4134, 1343, 3431, 4313, 1434, 4341, 3414, 4143, 4314, 3143, 1431

Five Notes* (my favorite): 13431, 34313, 43134, 31343, 14341, 43413, 34143, etc…

* not all possibilities listed

Longer Fragments

Step 1

Box off a larger group of notes and play in various combinations.

Step 2

Fiddle with the order of notes to yield and practice melodic fragments:

Further Development

To both the shorter and longer fragments, add slurs, articulations, accents, and character to experiment with expressivity.